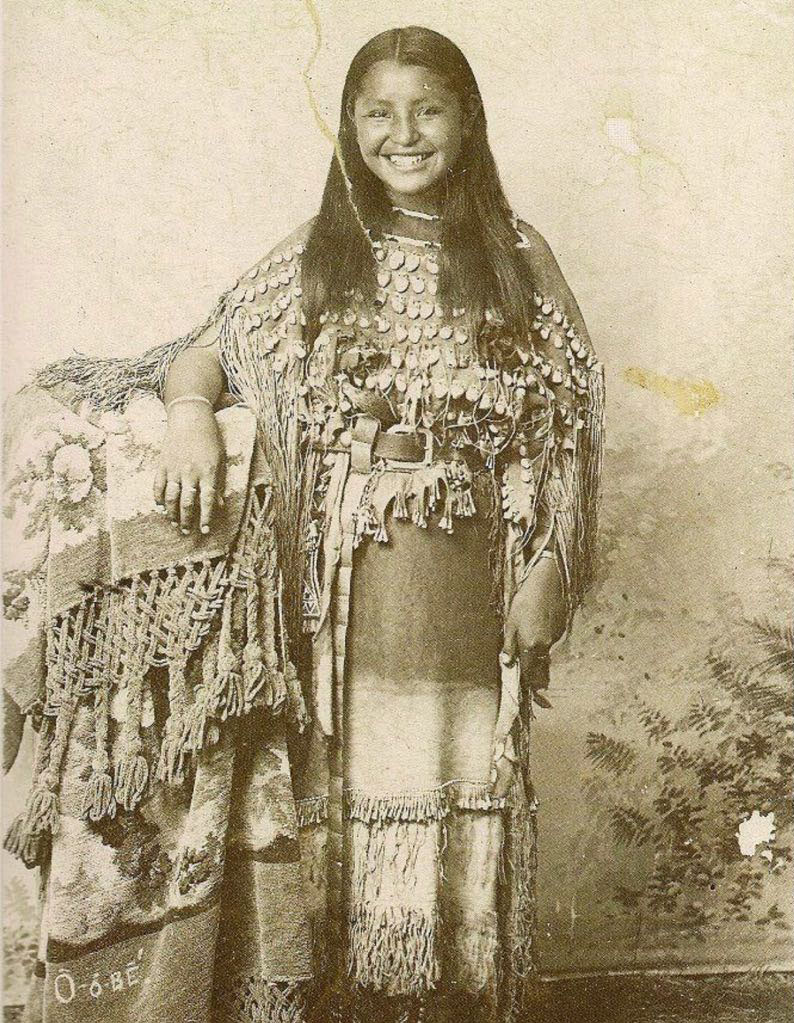

Simply take a look at this photo. Simply take a look at this younger woman’s smile. We all know her identify: O‑o-dee. And we all know that she was a member of the Kiowa tribe within the Oklahoma Territory. And we all know that the photo was taken in 1894. However that smile is sort of a time machine. O‑o-dee may simply as properly have donned some conventional/historic garb, posed for her buddies, and had them placed on the ol’ sepia filter on her camperiod app.

However why? What’s it in regards to the smile?

For one factor, we aren’t used to seeing them in previous photographs, especially ones from the nineteenth century. When photography was first invented, exposures may take 45 minutes. Having a portrait taken meant sitting inventory nonetheless for a really very long time, so smiling was proper out. It was solely close to the top of the nineteenth century that shutter speeds improved, as did emulsions, implying that spontaneous moments may very well be captured. Nonetheless, smiling was not a part of many cultures. It may very well be seen as unseemly or undignified, and plenty of people not often sat for photos anymanner. Photographs had been seen by many people as a “passage to immortality” and seriousness was seen as less ephemeral.

Presidents didn’t officially smile till Franklin D. Roosevelt, which got here at a time of nice sorrow and uncertainty for a nation within the grips of the Nice Depression. The president did it as a result of Americans couldn’t.

Smiling appears so natural to us, it’s arduous to suppose it hasn’t all the time been part of artwork. One of many first issues infants study is the power of a smile, and the way it can soften hearts throughout. So why hasn’t the smile been commonplace in artwork?

Historian Colin Jones wrote a complete e book about this, referred to as The Smile Revolution in Eighteenth Century Paris, begining with a 1787 self-portrait by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun that depicted her and her infant. Not like the coy half-smiles as seen within the Mona Lisa, Madame Le Brun’s painting confirmed the primary white, toothy smile. Jones says it brought on a scandal–smiles like this one had been undignified. The one broad smiles seen in Renaissance painting had been from children (who didn’t know wagerter), the “filthy” plebeians, or the insane. What had happened? Jones credits the change to 2 issues: the emergence of dentistry over the previous hundred years (including the invention of the toothbrush), and the emergence of a “cult of sensibility and well manneredness.” Jones explains this by looking on the heroines of the 18th century novel, the place a smile meant an open coronary heart, not a sarcastic smirk:

Now, O‑o-dee and Jane Austen’s Emma might need been worlds aside, however so are we–creatures of technology, smiling at our iPhones as we take another selfie–from that Kiowan girl within the Fort Sill, Oklahoma studio of George W. Bretz.

Be aware: An earlier version of this submit appeared on our website in 2020.

Related Content:

Take a Visual Journey Through 181 Years of Street Photography (1838–2019)

Ted Mills is a freelance author on the humanities who curleasely hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the professionalducer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can even follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his movies here.