Working a boring civil service job ill-suited to your talents doesn’t make you a author, however plenty of well-known writers have labored such jobs. Nathaniel Hawthorne worked at a Boston customhouse for a year. His pal Herman Melville put in considerably extra time—19 years—as a customs inspector in New York, following within the footsteps of his father and grandfather. Each Walt Disney and Charles Bukowski labored on the publish workplace, although not together (are you able to imagine?), and so, for 2 years, did William Faulkner.

After dropping out of the University of Mississippi in 1920, Faulkner grew to become its publishmaster two years later, a job he discovered “tedious, boring, and uninspiring,” writes Mental Floss: “Most of his time as a publishmaster was spent playing playing cards, writing poems, or drinking.” Eudora Welty characterized Faulkner’s tenure as publishmaster with the following vignette:

Allow us to imagine that right here and now, we’re all within the outdated university publish workplace and living within the ’20’s. We’ve come as much as the stamp window to purchase a 2‑cent stamp, however we see no person there. We knock after which we pound, after which we pound once more and there’s not a sound again there. So we holler his title, and ultimately right here he’s. William Faulkner. We interrupted him.… When he ought to have been placing up the mail and promoteing stamps on the window up entrance, he was out of sight within the again writing lyric poems.

By all accounts, she arduously overstates the case. As creator and editor Bill Peschel puts it, Faulkner “opened the publish workplace on days when it go well withed him, and closed it when it didn’t, usually when he needed to go hunting or over to the golf course.

He would throw away the advertising circulars, university bulletins and other mail he deemed junk.” A student publication from the time professionalposed a motto for his service: “Never put the mail up on time.”

Unsurprisingly, the powers that be eventually decided they’d had sufficient. In 1924, Faulkner sensed the tip coming. However reasonably than bow out quietly, as perhaps most people would, the long run Nobel laureate composed a dramatic and uncharacteristically succinct resignation letter to his superiors:

So long as I reside below the capitalistic system, I anticipate to have my life influenced by the calls for of moneyed people. However I can be damned if I professionalpose to be on the beck and name of each itinerant scoundrel who has two cents to spend money on a postage stamp.

This, sir, is my resignation.

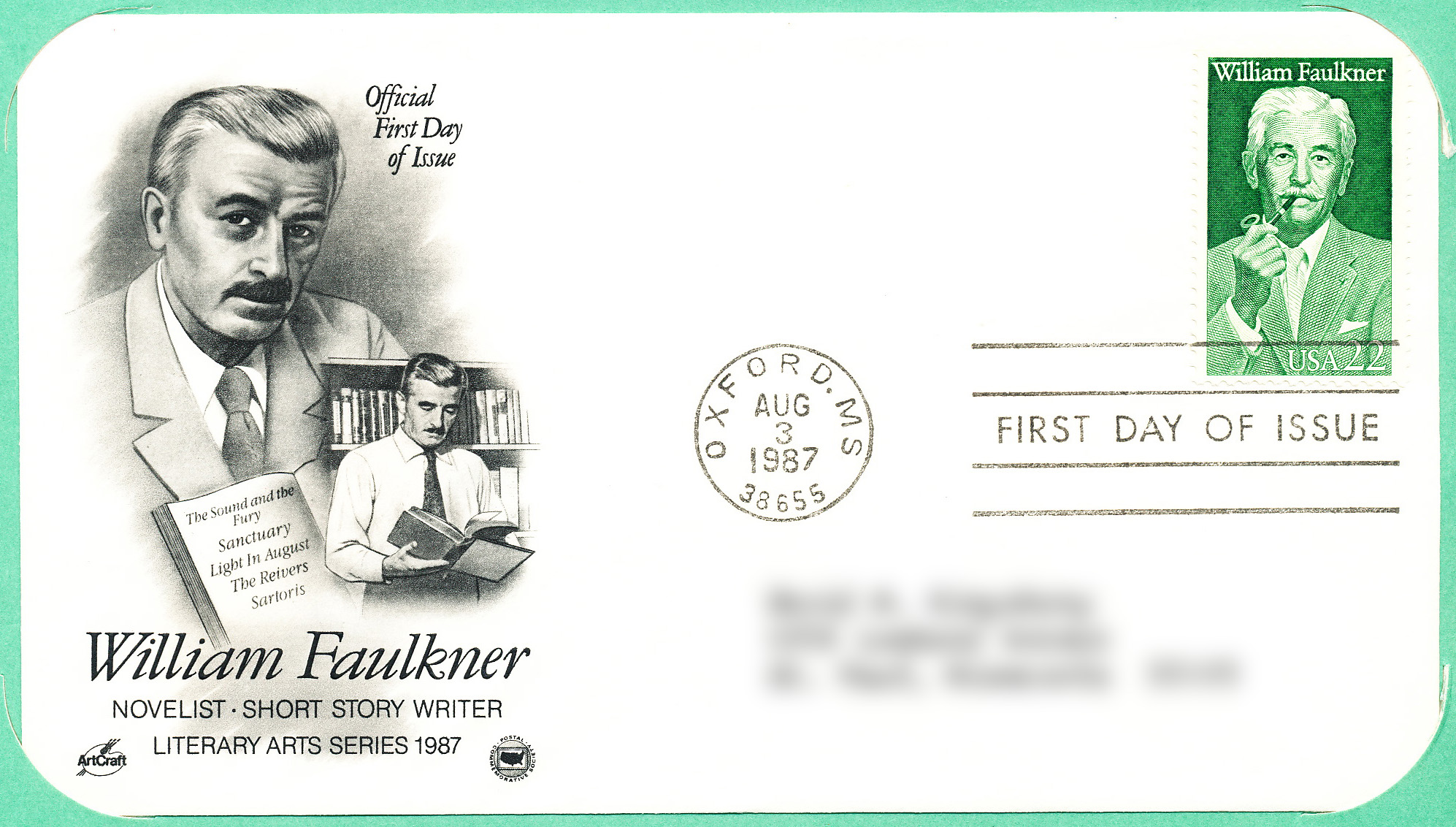

The defiant self-aggrandizement, wounded pleasure, blame-shifting… perhaps it’s these qualities, in addition to a notorious tendency to exaggerate and outproper lie (about his military service for examinationple) that so qualified him for his late-life profession as—within the phrases of Ole Miss—“Statesman to the World.” Faulkner’s present for self-fashioning might need go well withed him nicely for a profession in politics, had he been so inclined. He did, in spite of everything, receive a commemorative stamp in 1987 (above) from the very institution he served so poorly.

However like Hawthorne, Bukowski, or any number of other writers who’ve held down tedious day jobs, he was compelled to present his life to fiction. In a later retelling of the resignation, Peschel claims, Faulkner would revise his letter “right into a extra pungent quotation,” unable to withstand the urge to invent: “I reckon I’ll be on the beck and name of oldsters with money all my life, however thank God I gained’t ever once more must be on the beck and name of each son of a bitch who’s received two cents to purchase a stamp.”

Word: An earlier version of this publish appeared on our web site in

Related Content:

Seven Tips From William Faulkner on How to Write Fiction

William Faulkner’s Review of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea (1952)

Josh Jones is a author and musician primarily based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness